Contrary to popular belief, the most effective horror lighting isn’t about achieving perfect realism; it’s about deliberately manipulating the player’s brain.

- Hyper-realism often backfires, creating emotionally “dead” characters that break immersion by falling into the Uncanny Valley.

- True atmospheric design uses light and shadow not just to hide threats, but to guide player focus, control pacing, and create a state of perceptual unreliability.

Recommendation: Shift your design focus from simulating reality to curating a psychological experience, using light as a narrative tool to direct emotion and behavior.

As a level designer, I’ve seen countless teams chase the dragon of photorealism. The prevailing wisdom is simple: the more real the lighting, the deeper the immersion, the bigger the fear. We talk about ray tracing, global illumination, and physically-based rendering as the ultimate goals for creating a believable world. But this relentless pursuit of reality misses the true power of light in horror. It’s not a tool for simulation; it’s an instrument for psychological manipulation.

The goal isn’t to perfectly replicate how a flashlight beam cuts through a dusty corridor. It’s to weaponize that beam. It’s about crafting an experience where the player’s own perception becomes the antagonist. We establish rules of light and shadow only to subtly break them, creating a creeping dread that a simple jumpscare could never achieve. The most terrifying moments in horror games don’t come from what’s hidden in the dark, but from the dawning realization that you can’t trust what you see in the light.

This article moves beyond the technical and into the psychological. We will deconstruct the idea that realism is the final frontier. Instead, we’ll explore how to use light to play with the player’s cognitive biases, guide their movements without their knowledge, and create a sense of profound unease that lingers long after the screen goes dark. We will dissect why too much realism can be a curse, how to balance technical constraints with artistic intent, and ultimately, how to transform light from a visual element into a primary driver of player behavior.

This guide will take you through the core principles of using light as a psychological tool. We will explore the technical, artistic, and behavioral facets of atmospheric design, providing a comprehensive framework for creating truly impactful horror experiences.

Summary: The Psychology of Light: How Hyper-Realism Secretly Manipulates Player Behavior in Horror Games

- Why Too Much Realism in Lighting Can Make Characters Look Dead?

- How to Bake Global Illumination for Mobile Games Without Killing Battery Life?

- Lumen vs Baked Lighting: Which Workflow Saves More Dev Time?

- The Visibility Mistake: When “Realistic” Darkness Makes the Game Unplayable

- How to Use Subconscious Lighting Cues to Guide Players Through Complex Levels?

- Why AI Can Identify a Cat but Not Understand “Cuteness”?

- Voice Search vs VR Shopping: Which Trend Drives More Conversion?

- Virtual Simulations for Safety Training: Reducing Workplace Accidents by 30%

Why Too Much Realism in Lighting Can Make Characters Look Dead?

The pursuit of photorealism leads designers straight to the edge of the Uncanny Valley (UV), a concept that is absolutely critical in horror. This is the unsettling feeling we get when a character looks almost, but not quite, human. Hyper-realistic lighting is a primary contributor to this effect. When light perfectly models every pore and micro-expression but the underlying animation lacks the subtle, almost imperceptible chaos of real life, the result is a corpse-like automaton. The brain recognizes the visual data of “human” but the emotional data is missing, creating a disturbing cognitive dissonance.

This isn’t just a theory; it’s a measurable phenomenon. In fact, when faced with distinguishing between real and synthetic faces, recent perceptual studies reveal participants achieve only a 62% accuracy rate, showing just how fine the line is. For a game designer, falling on the wrong side of that line is catastrophic for immersion. Instead of feeling empathy or fear for a character, the player feels a clinical revulsion. A comprehensive review of UV research from 2007-2022 confirms that under current tech, the safest and most effective choice is finding a balance between high realism and deliberate abstraction to avoid the UV trap.

A viewer’s discernment for detecting imperfections in realism will keep pace with new technologies in simulating realism.

– Angela Tinwell et al., The Uncanny Valley in Games and Animation

Therefore, the artistic choice is not to perfectly simulate light, but to *stylize* it. Using techniques like subsurface scattering in a slightly exaggerated way can give skin a lifelike glow that pure physics might not. The goal is to create emotional realism, not physical accuracy. Light should serve the character’s emotional state, not the rigid laws of optics. This is where art direction triumphs over pure technical prowess, ensuring the player connects with a living being, not a beautifully lit mannequin.

How to Bake Global Illumination for Mobile Games Without Killing Battery Life?

Translating atmospheric lighting to mobile platforms is a unique challenge where performance is king. Real-time Global Illumination (GI) is often out of the question, as it would drain the battery in minutes. The solution lies in “baking” light—pre-calculating complex light interactions and saving them into textures (lightmaps). This provides the visual richness of GI with the performance cost of a simple texture lookup. However, a naive bake can still result in large file sizes and visual artifacts. The key is strategic optimization.

The first step is to be ruthless with what needs to be lit. Instead of a blanket approach, use baked lighting for the broad, static atmosphere and reserve any dynamic elements for only the most critical gameplay objects. This hybrid approach maintains mood without a constant high-performance cost. Use low-resolution lightmaps for large, distant surfaces and higher-resolution ones only where the player will be up close. This is a game of perceptual trickery: invest detail where the player looks, and save it everywhere else.

The following table provides a clear comparison of how different lighting techniques impact mobile performance. A hybrid model, combining the efficiency of baked GI with sparse dynamic lights, often presents the best compromise.

| Technique | Battery Impact | Visual Quality | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ambient Lighting | Low | Soft shadows, mood setting | Base atmosphere |

| Dynamic Lighting | High | Reactive, immersive | Key moments only |

| Baked GI | Very Low | Static but consistent | Mobile optimization |

| Hybrid Approach | Medium | Balanced quality | Modern mobile games |

Action plan: Auditing your mobile lighting strategy

- Light Sources Inventory: List every light source in your scene. Categorize them as ‘Atmospheric’ (static) or ‘Gameplay-critical’ (potentially dynamic).

- Performance Budgeting: Define a strict budget for dynamic lights. Limit them to player flashlights or key interactive elements that absolutely require them.

- Lightmap Resolution Triage: Review your lightmap resolutions. Downscale textures for any object that is far from the camera or not a focal point.

- Shader Complexity Check: Analyze your material shaders. Replace complex, multi-layered shaders on background objects with simpler, more performant versions.

- Fake vs. Real: Identify where a “fake” can work. Can a simple emissive texture or a vertex color gradient replace a costly light source to create a similar effect?

Ultimately, mobile lighting optimization is an art of illusion. It’s about knowing where the player’s attention will be and focusing your precious performance budget there, while using clever, low-cost tricks to fill in the rest. The result is a game that feels rich and atmospheric without melting the device in the player’s hands.

Lumen vs Baked Lighting: Which Workflow Saves More Dev Time?

The choice between a fully dynamic system like Unreal Engine’s Lumen and a traditional baked lighting workflow is one of the most significant decisions a development team can make. It’s often framed as a battle between visual quality and performance, but its most profound impact is on developer time and creative agility. There is no single answer; the “right” choice depends entirely on the project’s scale, team size, and design philosophy.

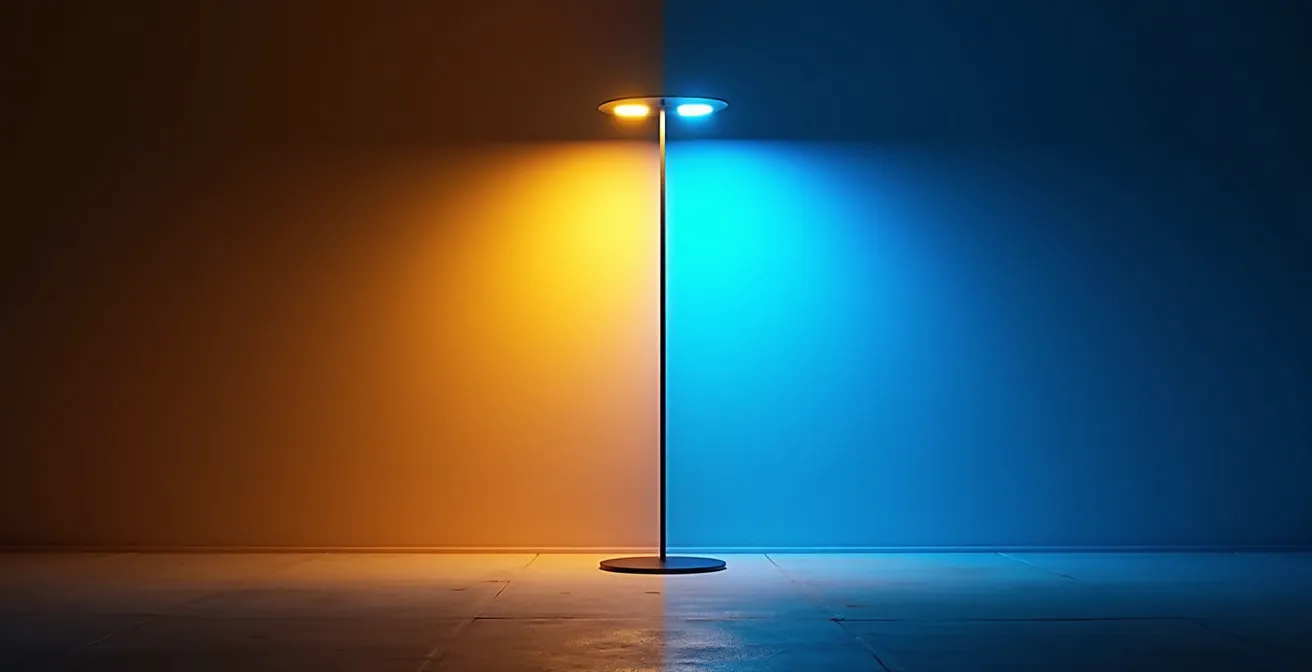

This image perfectly captures the dichotomy: on one side, the fixed, predictable, and performance-friendly world of baked lighting; on the other, the fluid, instant-feedback environment of real-time GI like Lumen.

Lumen and other real-time GI solutions offer an incredible advantage in the early stages of development: speed of iteration. An artist or designer can move a light source and see the final result instantly. This encourages experimentation and allows for the rapid discovery of atmospheric “happy accidents.” There are no hours-long bake times to wait for, meaning the creative flow is uninterrupted. For small teams or projects with a heavy focus on evolving environmental storytelling, this is a game-changer. The initial setup might be complex, but the time saved on iteration is immense.

Conversely, baked lighting demands a more methodical and planned approach. While the final result is highly performant and predictable across all hardware, the workflow is punishing. A single change to a light or object’s position can necessitate a complete rebake of the level, which can take hours or even days on complex scenes. This front-loads the design work, forcing artists to commit to lighting decisions early on. However, for large-scale projects aiming for broad hardware compatibility (like consoles and mid-range PCs), the performance guarantee of a static bake is invaluable. It saves countless hours of optimization down the line. The trend shows that with around 75% of developers likely to adopt nuanced lighting strategies, understanding this workflow trade-off is more critical than ever.

The Visibility Mistake: When “Realistic” Darkness Makes the Game Unplayable

There’s a common misconception among aspiring horror designers: darker is always scarier. This leads to the “visibility mistake,” where levels are plunged into a “realistic” darkness that is not just atmospheric but actively frustrating. When players spend more time bumping into walls than engaging with the horror, immersion is shattered. The fear of the dark is a powerful tool, but it relies on the *suggestion* of what might be in the shadows, not the literal inability to see. True horror lighting is a delicate balance between obfuscation and readability.

The Psychology of Perceptual Darkness

Darkness in games works by increasing the player’s cognitive load. As one analysis points out, darkness takes away clarity, it adds confusion and uneasiness. The brain is forced to work harder to interpret the environment, which heightens feelings of vulnerability and tension. However, there’s a tipping point. When the cognitive load becomes too high (i.e., the screen is just black), the brain disengages. The goal is not absolute darkness but *perceptual darkness*—an environment with just enough visual information to let the player’s imagination fill in the terrifying blanks.

Community feedback consistently reinforces this point. While players appreciate mood, they despise unfairness. Data from player feedback shows that while dim light enhances fear, according to 67% of contributors, they also expect clear visual language that allows for navigation and interaction. A well-lit “safe” area, a flickering light that draws attention to a key item, or a moonbeam that subtly reveals a path are not crutches; they are essential tools of narrative guidance. They are promises made to the player: “we want you to be scared, but we don’t want you to be lost.”

The solution is to design with “graded” darkness. Instead of a binary on/off state, create zones of varying visibility. Use ambient light, bounce lighting, and emissive materials to ensure that even the darkest corners of a level have some readable shape and form. Your primary light sources should be used to direct attention and create contrast, not as the sole means of illumination. The goal is to make the player *feel* like they’re in oppressive darkness, while secretly giving them all the visual cues they need to navigate the world.

How to Use Subconscious Lighting Cues to Guide Players Through Complex Levels?

The most elegant level design uses light not as a spotlight, but as an invisible hand guiding the player. This is the art of subconscious guidance, where color, intensity, and movement are used to pull a player’s attention toward a path or objective without them ever consciously realizing they’re being led. It’s a form of visual storytelling that respects the player’s intelligence while ensuring they don’t get lost or miss critical narrative beats. This goes far beyond the obvious “flickering light over the key.”

This is where light becomes a character in itself, a silent narrator. A single, warm light in an otherwise cold, blue-hued environment acts as a psychological magnet, promising safety or interest. The human eye is naturally drawn to warmth and contrast. We can use this to our advantage, creating a “breadcrumb trail” of light that leads the player through a complex layout. This doesn’t have to be overt; a slightly brighter texture on a distant wall, a subtle god-ray pointing towards a doorway, or a change in color temperature can be enough to nudge the player in the right direction.

The psychology of color plays a huge role here. As noted in game design research, a restricted, monochromatic palette can create feelings of melancholy, while a sudden shift to a garish, unnatural color can signal danger or otherworldliness. According to a guide on horror lighting, this technique can be used to direct focus; for example, you may use a spotlight to emphasize a shock or a flashlight beam to expose a hidden object. This is about establishing a visual language. If the player learns early on that a faint green glow signifies a health pack and a pulsing red light signals an enemy patrol, you can communicate complex information instantly and without a single line of text.

This method builds a deep sense of trust and flow between the designer and the player. The player feels smart for “discovering” the path, while the designer maintains narrative control. It’s the most powerful and respectful way to use light: not just to illuminate, but to communicate.

Why AI Can Identify a Cat but Not Understand “Cuteness”?

This question gets to the heart of the limitations of pure simulation, which is a powerful analogy for lighting design. An AI can be trained on millions of images to identify the patterns that constitute a “cat” with near-perfect accuracy. It recognizes features: pointy ears, whiskers, fur texture. However, it has zero comprehension of “cuteness.” Cuteness is not a pattern; it is a subjective, emotional, and contextual human response. The AI identifies the *what*, but is completely blind to the *why* and the *how it feels*.

This is precisely the trap of hyper-realistic lighting. A rendering engine can perfectly simulate the physics of light bouncing off a surface, identifying every material property with scientific precision. But it cannot understand the *emotional context* of that light. It cannot know that a cold, sterile light in a hospital setting evokes feelings of dread and isolation, while the same intensity of light, if warm and flickering from a fireplace, evokes comfort and safety. This is where the designer’s brain must intervene.

Cognitive science provides a clue. When we observe something, our brain doesn’t just process visual data; it tries to match that data with its expectations of how that thing should behave. As cognitive scientist Ayşe Pınar Saygın found in a study on the Uncanny Valley, “The brain doesn’t seem selectively tuned to either biological appearance or biological motion per se. What it seems to be doing is looking for its expectations to be met – for appearance and motion to be congruent.” When there is a mismatch—like a hyper-realistic character that moves stiffly—the brain flags a “perceptual conflict.” This is exactly what happens when lighting is technically perfect but emotionally tone-deaf.

Just as an AI can’t grasp cuteness, a rendering engine can’t grasp “eeriness” or “hope.” These are not properties of light; they are feelings evoked in a human mind by the *artistic application* of light within a specific context. Our role as designers is not to be a better physics engine, but to be the interpreter of emotion, using light to tell a story that the code itself could never understand.

Voice Search vs VR Shopping: Which Trend Drives More Conversion?

At first glance, this comparison seems unrelated to horror game lighting. However, it provides a crucial lesson in immersion and user interface. Both Voice Search and VR Shopping aim to create a more natural, immersive “conversion” experience—one by removing visual friction, the other by maximizing it. The success or failure of each hinges on how well they manage the Uncanny Valley of interaction. This offers a direct parallel to the challenge of creating believable characters and environments in games.

Voice Search attempts to bypass the Uncanny Valley entirely by being non-visual. It’s an abstract interface. VR Shopping dives headfirst into it, attempting to simulate the physical act of browsing. The trend that “drives more conversion” is the one that best avoids creating a jarring disconnect between the user’s expectation and the system’s execution. A clunky VR interface that’s hard to navigate is just as off-putting as a voice assistant that constantly misunderstands you.

This is precisely the problem faced by early attempts at hyper-realism in games. Landmark titles like *L.A. Noire* used groundbreaking facial capture technology, but the result often fell into the Uncanny Valley. The faces were incredibly detailed, yet the eyes felt lifeless, creating a subtle but persistent disconnect for the player. The technology was impressive, but the emotional congruence was not always there. This is the VR Shopping problem: the attempt at high-fidelity simulation exposed the small imperfections, which became more glaring as a result.

In contrast, modern titles like *The Last of Us Part II* or *Detroit: Become Human* learned this lesson. They used extensive motion capture not just for the big movements, but for the micro-expressions and subtle shifts in gaze that convey emotion. They understood that immersion comes from the holistic performance, not just the surface detail. Their success lies in ensuring that the visual realism is perfectly matched by behavioral realism, creating a believable whole. They solved the Uncanny Valley problem not by adding more polygons, but by adding more humanity.

Key Takeaways

- Effective horror lighting is a tool for psychological manipulation, not just realistic simulation.

- The Uncanny Valley is a major risk of hyper-realism; emotional congruence is more important than physical accuracy.

- Player guidance through subconscious lighting cues (color, contrast) is more elegant and immersive than overt signs.

Virtual Simulations for Safety Training: Reducing Workplace Accidents by 30%

The principles of manipulating player behavior through lighting are not confined to entertainment; they have profound real-world applications, most notably in virtual simulations for safety and stress training. By creating hyper-realistic, high-stress scenarios in a safe virtual environment, industries can train personnel to react correctly under pressure. The goal is not just to teach a procedure but to inoculate the trainee against the panic and cognitive overload that occur during a real crisis. Here, the lighting is not just atmospheric—it is a core part of the training mechanism.

In these simulations, lighting is used to intentionally induce stress. A sudden power failure, flickering emergency lights, or smoke obscuring vision are all controlled events designed to trigger a physiological fight-or-flight response. By repeatedly exposing trainees to these stressors in a controlled way, the simulation helps build “stress resilience.” The trainee learns to perform complex tasks and make clear decisions even when their senses are being deliberately assaulted. It’s the ultimate expression of using light to modify behavior, with the goal of saving lives.

This concept of stress inoculation is something horror game designers have been mastering for years, whether they realize it or not. The experience of a player navigating a terrifying, dimly lit environment is a form of low-stakes stress training.

With its seventh mainline entry, Resident Evil opted for something completely different, delivering one of the more frightening installments. 2017’s Biohazard became a first-person survival horror influenced by games like Amnesia and Outlast. Playing as Ethan Winters searching for his wife Mia, you’ll immediately see why this game works best in the dark from the opening moments, which feature jump scares tied to lighting cues and a found-footage mechanic.

– Player Experience with Horror Game Stress Training

This highlights the ultimate potential of our craft. When we move beyond thinking of light as mere decoration and begin to understand it as a language that speaks directly to the player’s nervous system, we unlock a new level of design. We are not just creating scary games; we are crafting intricate psychological experiences that can shape reactions, control focus, and build resilience. It’s a testament to the power of using light not to show a world, but to shape the mind of the person experiencing it.

Frequent questions about How Hyper-Realistic Lighting Changes Player Behavior in Horror Games?

Why do horror games recommend playing with lights off?

Playing with the lights off removes external visual distractions, allowing the player to become fully immersed in the game’s world. The intricately crafted lighting effects and jump scares are more effective because they feel more as though you’re witnessing the scary moments first-hand, heightening the sense of presence and vulnerability.

How does darkness affect player stress levels?

Games use darkness to trigger genuine physiological fight-or-flight responses. By limiting visual information, the brain’s threat-detection systems become more active, increasing heart rate and alertness. This serves as a form of stress inoculation training, conditioning the player to manage anxiety in a controlled environment.

What’s the difference between absolute and perceptual darkness?

Absolute darkness is a completely black screen, which is often frustrating and breaks gameplay. Perceptual darkness is an artistic technique where the environment is very dark but still contains subtle visual information—faint ambient light, silhouettes, or textures. This allows the player’s eyes to “adapt” and their imagination to fill in the gaps, making darkness a manageable and tense gameplay element rather than a simple obstruction.